Ahead of her ground-breaking show, Lady Gaga fans spent days on a sidewalk trying to see their diva at the Copacabana Palace hotel, in Rio de Janeiro. So when a delegation of black cars with police escort showed up, they went wild, and then quickly disappointed upon seeing the car passengers wearing just regular suits: Sharing the iconic beach front hotel with the pop star were BRICS+ delegates, in Rio for a smorgasbord of meetings. (Quick detour: Gaga later made it up to them sending 80 pizzas to her adoring fans camped outside.)

Building BRICS+

I have always been fascinated by this ad-hoc group. From the 2001 investment report by Goldman Sachs, to a 2006 conversation between the leaders of Brazil, Russia, India and China, then the 2011 addition of South Africa, followed by the creation of their own development bank— the NDB— in 2015, leaders of this heterogenous grouping made it not only work but live this long, and grow. In 2024 it went from five to 11 members and nine partner countries, ranging from Bolivia to Kazakhstan. It became even more puzzling — 20 nations that have very, very different priorities, issues and allegiances coming together. What are they aiming at? What can the BRICS+ deliver different than the G20, G77, or the UN itself?

Never the main platform for any of the members, the partnership always seemed more like a “good thing to have.” It was nonetheless useful in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, when members voted together within the IMF in the push for some of the (timid) reforms made at the time, Professor Luiza Peruffo at University of Rio Grande do Sul told me.

Membership in the group also helped Russia find a semblance of not being completely isolated at the onset of the war against Ukraine. “It follows the logic of diplomacy to look for allies,” said Laura Waisbich, programs director at Igarapé Institute, “but any agreement can only come as a consensus, and the enlarged group makes it that much harder to find the lowest common denominator.”

Rotating presidency

The popular policy of rotating the presidency of multilateral groupings rendered Brazil in a busy spot, leading the G20, BRICS summit and COP 30 in a row. And after the relative success of the G20 summit in Rio in 2024, expectations are high for a repeat of an agreed-upon communiqué out of the next two meetings.

Brazil wants a few things from this BRICS+ summit. First, to gather support and, hopefully, a consolidated front toward a successful COP30. Then there are the topics of global health, artificial intelligence governance, peace and security architecture, and the institutionalization of the group itself. (Though the agenda presented by Brazil may not stop other members from bringing issues such as tariffs to the forefront.)

The initial sign of the stalemate-status that the enlarged group might render going forward came at the very first meeting of the (now) 11 foreign ministers: the forever-quest of reform of the UN Security Council failed to get all new members to agree on the wording around it. Until last year, when the group had only five letters, Brazil, India and South Africa hoped for the support of partners China and Russia in their candidacy for an enlarged Security Council.

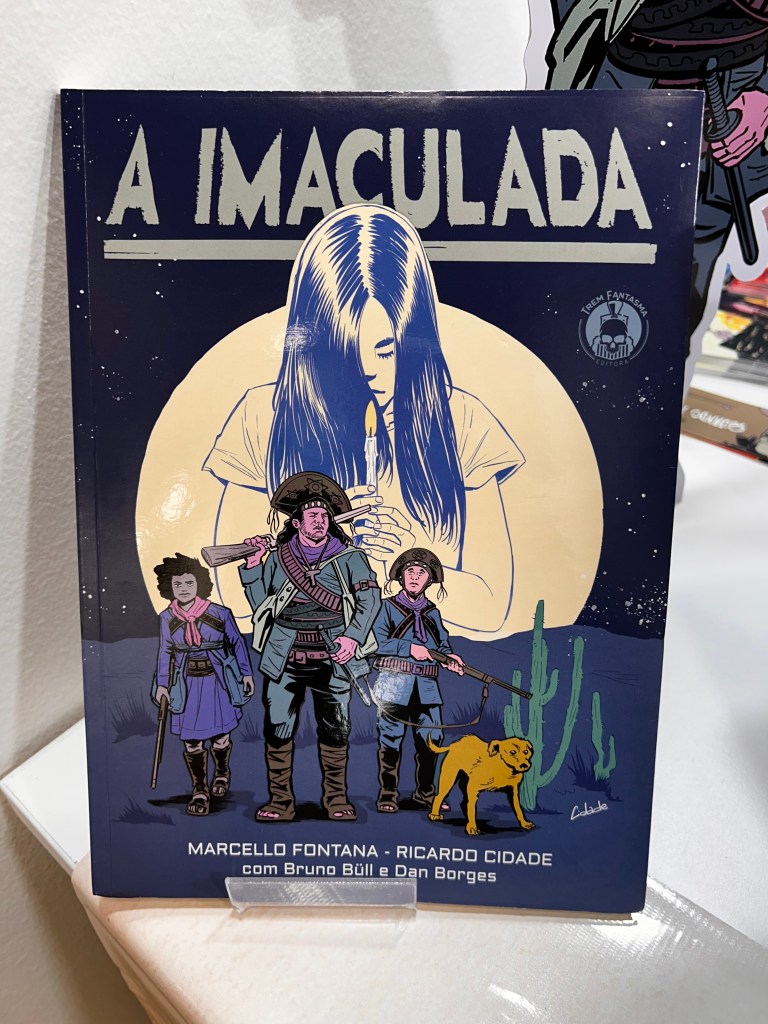

Photo Credit: Isabela Castilho | BRICS Brasil

Now, with many more letters in the acronym, the plea did not go well with new members Egypt and Ethiopia, that would prefer not to see South Africa as the flag bearer for the whole continent. That meeting of foreign ministers was expected to draft the communiqué for leaders to sign in July, but ended with just a few words from the host nation highlighting Brazil’s hopes and dreams for the Summit.

Regional disputes and the lack of common interests and priorities aren’t the only hurdles facing BRICS+. Countries at war and governments that question the right to exist of other nations coming together to discuss peace also raises questions about the validity of their words.

There’s more to collaboration

Despite the early setback, BRICS+ representatives are holding conversations on just about everything: there is a sports task force, and anti-corruption working group, discussions on artificial intelligence governance, meetings of health ministers, webinars for youth representatives, cooperation towards energy transition and mineral research to mention a few examples of the gamut of topics and areas where this enlarged —and still odd—group is looking to collaborate on. In April, Agriculture ministers — representing a third of the planet’s arable land and fresh water reserves — were indeed able to reach a joint declaration focused on cooperation during emergencies, collaboration towards infrastructure and reducing inequality in rural areas, among other topics.

As odd as the group is when it comes to geopolitics and domestic policies and priorities, most (of us) share a reality: inequality, vulnerability to climate events, and the not always geographically accurate label of Global South. Will that be enough to render the + sign in the acronym the right move for the group? Well, we need to wait for July.